What can a 4,000-year-old bone tell us about power, family, and social hierarchy? For archaeologists studying Shimao – one of China’s earliest cities – the answer used to be limited to tomb layouts and burial goods. Now, ancient DNA sequencing is transforming these silent remains into detailed family trees spanning up to four generations, revealing insights about marriage patterns, inheritance, and the social structures of early civilizations.

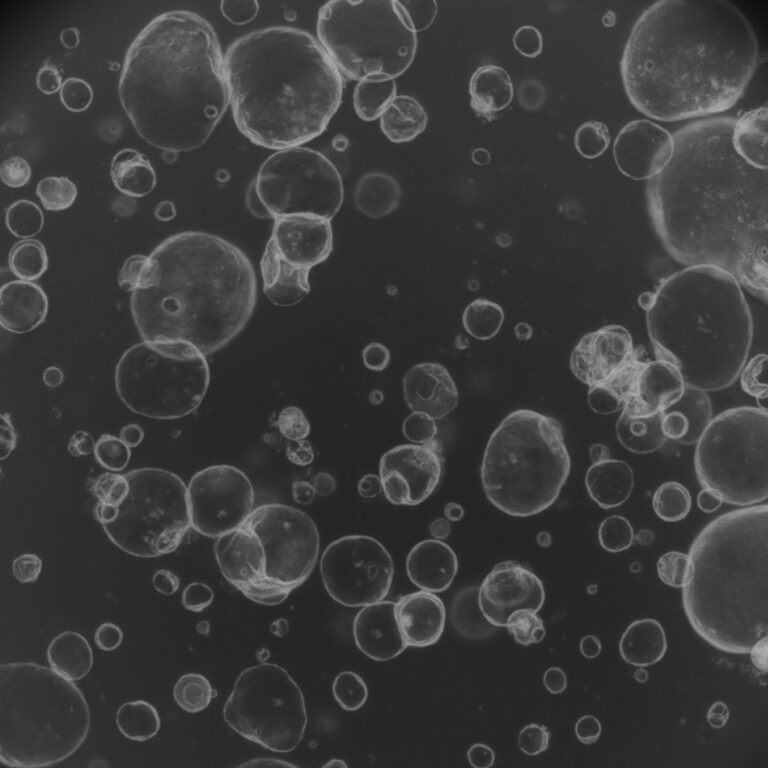

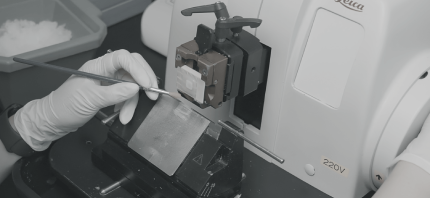

Researchers sequenced 144 ancient genomes from Shimao and surrounding sites, reconstructing pedigrees that indicate predominantly patrilineal descent. By extracting degraded DNA from bone powder and applying sophisticated analyses – including kinship mapping, identity-by-descent tracking, and mitochondrial DNA sequencing -scientists could trace both male and female lineages, uncovering patterns invisible to archaeology alone.

image: freepik

The genetic data revealed unexpected findings. Sacrificial victims at the East Gate, previously assumed to be mostly female, were found to be almost entirely male. In contrast, some elite burial sites included female sacrificial remains, suggesting that ritual practices varied depending on social context.

Shimao’s material culture, including bronze tools and jade from distant regions, shows extensive trade networks. Yet the genomes indicate that the core population maintained continuity with local Yangshao-related ancestors, demonstrating that ancient societies could engage in long-distance exchange while preserving social and genetic boundaries.

This is genomic archaeology in action: using DNA to reveal the invisible structures of ancient societies. Every burial becomes a potential archive, and every bone a manuscript, offering new perspectives on how real people navigated power, family, and social hierarchy.

Read more:

- Ancient DNA from Shimao city records kinship practices in Neolithic China

- Nature’s Blueprint: Biotechnology Reshaping Our Sustainable Future

- Epigenetics and Healthy Eating Habits | Insights from ODC 2025