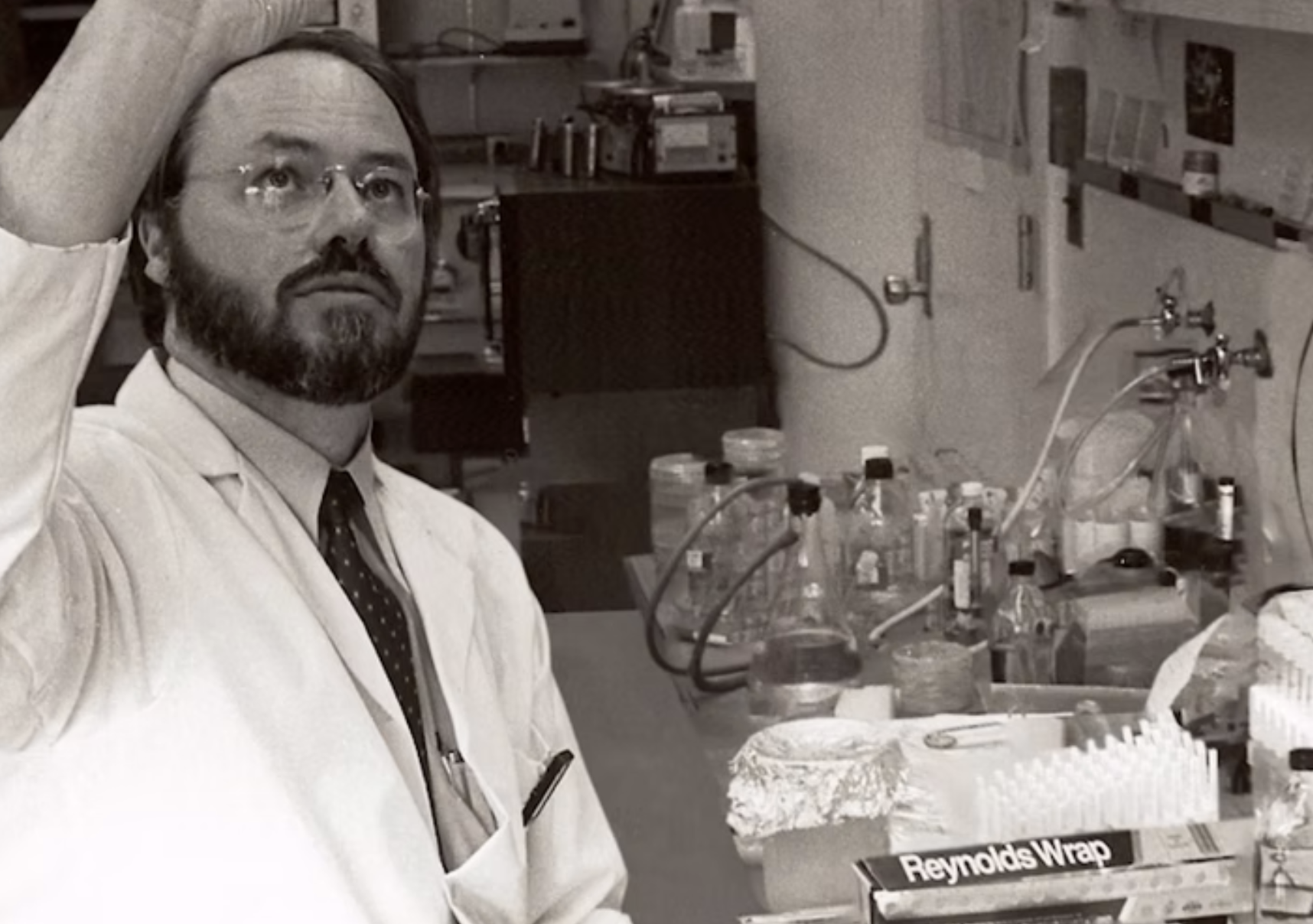

At the ODC25 conference, Dr. Choong-min Ryu from Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB) shared insights that challenge how we think about life itself. His work bridges an interesting gap between traditional reductionist biology and a more integrated understanding of living systems.

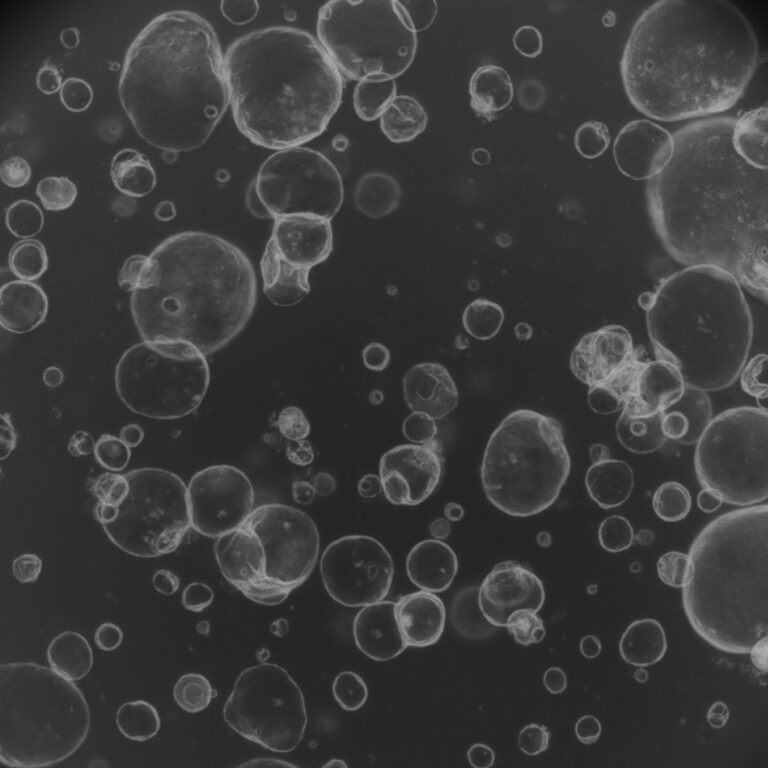

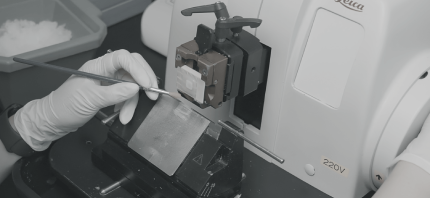

Western science has typically approached life by breaking it down into smaller components – from organs to tissues to DNA. Organoid research, which reconstructs organs from tissue, seems to reverse this process. Dr. Ryu contrasted this with an ancient Eastern perspective from the Book of Changes: life is defined by continuous adaptation to change rather than by its smallest parts.

This brings us to the holobiome – the idea that microorganisms and their hosts should be studied as a single integrated system rather than separate entities. The reasoning is straightforward: microorganisms appeared on Earth about 3.5 billion years ago, roughly 2.5 billion years before plants emerged. Every complex organism that evolved afterward developed in the presence of microbes.

From this perspective, the question isn’t whether humans can live without bacteria – we simply cannot. The relationship is fundamental rather than optional.

Learning from Ecological Relationships

In nature, species compete until they find ways to coexist. This principle, known as niche differentiation, applies equally to microbial communities. Interestingly, more than 90% of microbes appear to be beneficial or neutral; disease-causing microbes are exceptions rather than the rule. Dr. Ryu’s research on plant-microbe interactions illustrates this well. When greenhouse whiteflies attack pepper plants, the plants respond by growing larger roots and recruiting specific bacteria like Pseudomonas from the soil. These bacteria then help defend against the insects. The plant essentially communicates with its microbial partners through chemical signals.

Similarly, in agriculture, the relationship between humans and microbes is often competitive – we both want the same food resources. Our use of pesticides has led to an evolutionary arms race, with microbes developing resistance over time. The interactions grow increasingly complex as both sides adapt.

Clinical Observations

Some recent findings are particularly intriguing. A study of intensive care patients at Severance Hospital found a correlation between microbial diversity and survival rates. Patients with higher microbial diversity showed better outcomes, though much work remains to understand the causal mechanisms.

There are also emerging observations about the gut-brain connection. Some patients with Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, or autism who receive antibiotics for abdominal pain report improvements in their neurological symptoms as well. While these are preliminary observations, they suggest that gut microbiota may influence brain function in ways we don’t yet fully understand.

Future Directions

The challenge now is identifying which microbes matter most. Dr. Ryu proposes focusing on “connector” microbes – those that interact broadly with many other species. If we can identify and characterize these key players, it might be possible to develop more targeted probiotic interventions.

This kind of analysis is currently difficult due to the complexity of microbial communities. However, advances in computing power and AI may make it feasible in the coming years.

Broader Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated both our vulnerability to harmful microbes and our capacity to respond through science. The development of mRNA vaccines showed what’s possible when we properly distinguish between infected and healthy states.

As biotechnology continues to advance, Dr. Ryu raised a question worth considering: if we develop the ability to significantly extend human lifespan or even overcome aging, should we? Science often focuses on what’s technically possible without necessarily addressing whether something should be done. These are questions that extend beyond biology into ethics and philosophy.

Dr. Ryu’s work reminds us that we are not isolated individuals but ecosystems composed of countless organisms. Understanding this relationship better – through the lens of the holobiome – may lead to new approaches in medicine, agriculture, and our general understanding of life. The ancient wisdom that “when this exists, that exists” appears increasingly relevant as we uncover the deep connections between organisms and their microbial partners. There is much still to learn, but the direction seems clear: coexistence rather than conquest may be the more productive framework for our relationship with the microbial world.

About Organoid Developer Conference

ODC (Organoid Developer Conference; website: https://odc.network/) is a visionary platform that paves the way for a sustainable future through organoid technology. By blending scientific innovation with artistic creativity, the event aims to unlock new possibilities and inspire transformative advancements.

Since its inception in 2018 as a symposium hosted by OrganoidSciences, Inc. in Korea, ODC has grown into a dynamic hub connecting over 1,000 institutions worldwide. It’s a place where curious minds – scientists, artists, philosophers, and everyday innovators – come together to share groundbreaking research, spark creative inspiration, and shape the future of bioscience.

Read more:

Epigenetics and Healthy Eating Habits | Insights from ODC 2025

ODC25 Session 08 – The Age of Artificial Organs, Organoids

ODC 2025 – A Festival of Science, Art & Culture

The Clean Girl Aesthetic: How Science, Skin Biology, and Organoids Shape Modern Beauty