The most frightening moments in Stranger Things are not the monsters. They are the silences before them – the memories, the grief, the unresolved trauma that quietly isolates each character long before Vecna appears.

Vecna does not hunt at random. He targets those already under immense psychological strain, as if trauma itself has weakened the boundary between worlds. What the series frames as supernatural horror is, in many ways, a powerful metaphor for something deeply biological: chronic stress.

Image: Netflix

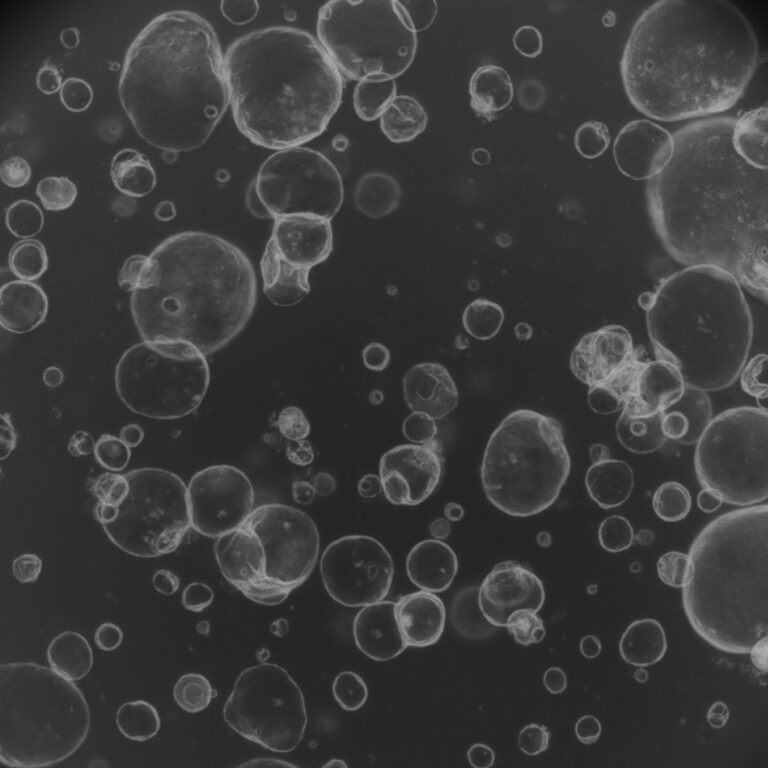

In human biology, stress is not just an emotional response. When prolonged, it reshapes hormonal signaling, disrupts immune balance, and accelerates cellular aging. The body does not simply recover from stress – it adapts to it, often at a cost. Over time, this sustained pressure can manifest in neurodegeneration, inflammatory conditions, skin dysfunction, and premature aging.

What Stranger Things captures so precisely is that trauma is not a single event. It is a persistent biological state. Yet in preclinical research, stress is frequently reduced to a short-term stimulus or ignored altogether. Conventional animal models struggle to reflect the duration, emotional context, and system-wide effects of human trauma. Stress becomes a variable to control, rather than a condition to understand.

Human-relevant models offer a different perspective. By preserving human tissue architecture, cell-cell communication, and stress-responsive pathways, advanced in vitro systems enable researchers to study how chronic stress reshapes biology over time – across interconnected systems, not isolated cells.

The Upside Down is unsettling because it feels familiar, yet fundamentally altered. Chronic stress does the same to human biology. It doesn’t create monsters. It transforms what already exists.

Read more: